A New Perspective on Homelessness, from 2003

During his short yet impactful career, Satoshi Kon redefined the culture of Japanese anime filmmaking. His works were marked by a complex duality that delicately blurred the boundaries between reality and fantasy. In 2020, after his death, the industry honored Satoshi Kon—who had directed Tokyo Godfathers—with an Annie Award. In that film, he portrayed the everyday reality of homelessness, enriched with the wonder of fantasy—and revealed a side of Tokyo that is rarely seen.

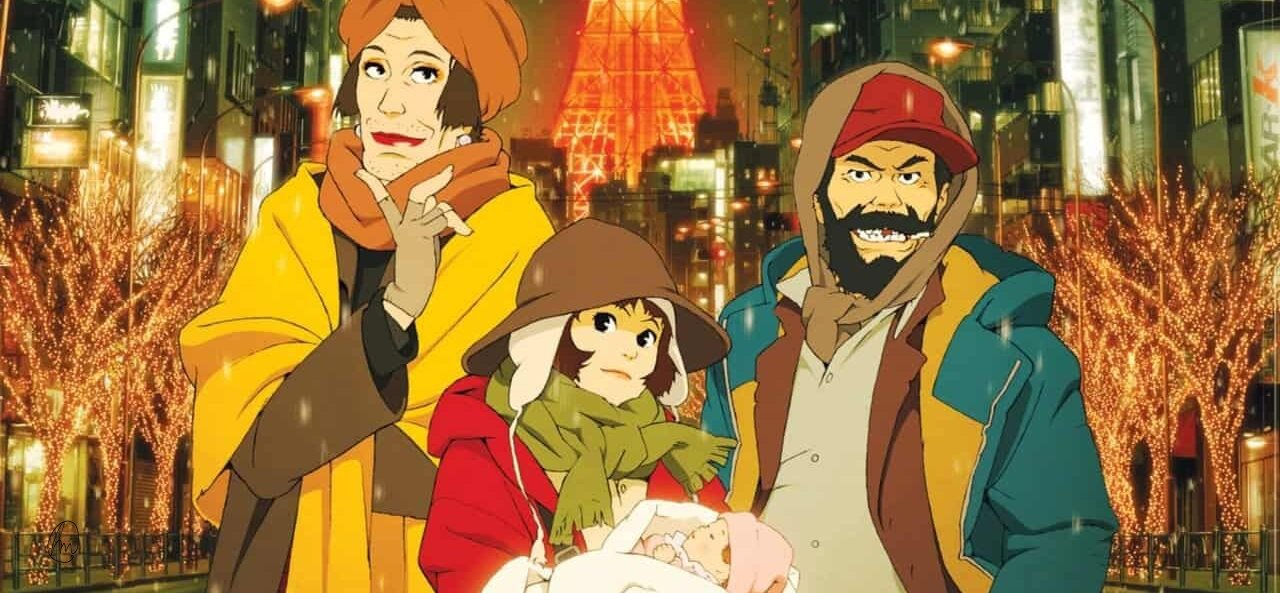

Tokyo Godfathers

Released in 2003, Tokyo Godfathers is a rare gem in the anime world—both written and directed by Satoshi Kon—and is unquestionably a film worth seeing. The art direction was handled by Shôgo Furuya, whose previous work includes acclaimed titles such as The Wind Rises, From Up on Poppy Hill, and Spirited Away.

Even this brief list of credits may signal to anime-savvy viewers that they’re in for something truly exceptional—and for those new to this world, it’s worth trusting the names behind the film and reading on to discover why Tokyo Godfathers stands out.

Story

On Christmas Day, three homeless characters meet:

Gin – a down-and-out alcoholic, a pessimistic realist.

Hana – a big-hearted drag queen haunted by her past, but above all, deeply human.

Miyuki – a runaway teenager, proud, wounded, and brimming with attitude.

They discover an abandoned baby in a Tokyo landfill. From that point forward, the film follows their chaotic wanderings through city’s shadowy corners in search of baby Kiyoko’s origins. Throughout the challenges and adventures, the characters’ past memories begin to echo through each other’s lives—their paths overlapping and gradually weaving together. In doing so, the film presents a rarely seen perspective on the lowest rungs of Japanese society: homelessness, as portrayed in animation like never before.

Homelessness from a New Angle

This was the first anime to place socially marginalized individuals at its center with such unflinching realism. It portrays their exclusion, the circumstances and choices that drove them to the streets, and the decisions that pushed them to society’s edge—but also the deeply human, moral choices they make for the baby’s sake.

Tokyo as We’ve Never Seen It

It’s fascinating to see a wintry Tokyo rarely shown in tourist brochures—an aesthetic choice that added significant complexity to the film’s production. In a previous interview, Shôgo Furuya explained that snow-covered landscapes in anime had typically been rendered as flat, white surfaces. But Tokyo Godfathers departed from that convention.

Since most scenes take place on snowy nights—and Japanese cities are famously filled with vending machines that cast vertical beams of light, which add depth and bring out the snow’s texture in remarkable detail—drawing it required a much more nuanced visual approach. Capturing winter in such rich detail meant layering subtle shades of white over one another—a painstaking artistic effort that tested the production team’s precision at the highest level.

Another major visual hurdle was the use of realistic, eye-level Tokyo cityscapes that pull the viewer directly into the action. Each location was based on an actual place in the city, carefully modeled through field visits and countless photographs. Achieving this level of realism required meticulous, almost obsessive observation.

In many cases, the team revisited the same locations multiple times to capture every last detail with precision.

Motifs

One of the film’s central visual elements is the world of garbage dumps scattered across Tokyo, packed with translucent plastic bags—drawn with an extraordinarily high level of artistry. These were made perfectly transparent using digital techniques. Moreover, one of the director’s key recurring motifs is the image of trash bags thrown onto the streets, which serves as a symbolic parallel to the three homeless protagonists. Their individual backstories—and Hana’s emotionally charged remarks to Gin—only deepen the image Gin has of himself as someone discarded and left behind.

The act of “cleaning up” garbage, the duality of cruelty and compassion—all of it is conveyed through a magical narrative rendered in strikingly realistic terms.

Why You Should Watch It in the Original Japanese

The 88-minute film is best watched in its original Japanese with subtitles, as the voice actors are an essential part of the unfolding story. The intonation and the soul breathed into the animated characters truly come alive only in the original language—this is what gives the film its true richness and diversity. A striking example is the final word, Otosan (father), delivered by voice actress Aya Okamoto in a way that leaves the ending emotionally open. Unfortunately, subtle nuances like this—along with the importance of vocal tone—are often lost in dubbed versions, especially in films like Tokyo Godfathers.

Source: Making of Tokyo Gdofathers 1-2, Satoshi Kin Winsor McCay award 2020, McGill.ca- Cityscaope of Trash: The Nocturnal Tkyo of Tokyo Godfathers

Iamges: all rights reserved Satoshi Kon Mad Hous production.

If you’d like to stay up to date with more interesting reads like this – or just relax with some laid back culture content – feel free to subscribe to the newsletter at the bottom of the page. If you do, please make sure to check the spam folder too, since the confirmation email might end up there. Agh, and don’t worry you will get news from the Heti Mocsok only twice a month!